Rustlers

by Joe McCarter (In His Father's Voice)

A fall or two before Janey and I was married, I got into the middle of one of the damndest deals you ever seen. It'll take a while to tell it because a lotta things people did and said never made much sense but, anyway, here it is.

I was helping out Pete and the ol' man some with their cattle as well as lookin' after my own stuff. I'd rented the Hot Springs hunert and sixty from Card, and I had went 50-50 on Frank and Charley Trader's cattle – only a hundert head or so – but findin' feed was gettin' harder ever' year with the country settlin' up and, what with more sheep ever' year, I kept pretty busy.

We were luckier than some with summer range as the ol' man had always ran back between the South and Middle Forks of Lime Creek, and Jack Skillon had lost a band of bucks on the east side of Cold Spring Ridge from poison a few years back and most sheepmen were pretty leary of all that country. Card and me were sorta runnin' ours with Pete's and the ol' man's and it hadn't worked out too bad so far.

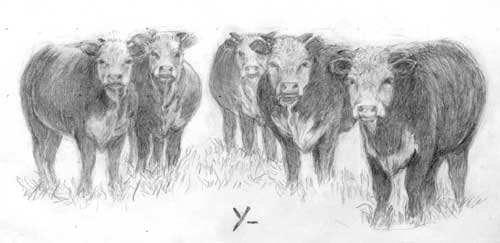

Orla "Pete" McCarter's Cattle by Irma McCarter Petrick

The Prairie itself was damn near all fenced now. There was a homestead shack of some kind on about ever' quarter section. They were all tryin' to dry farm of course and some of the better ones – usually Palousers (anybody from Washington State was called Palousers) that had some practice at it and understood how to summer fallow and grow fall grain – weren't doin' too bad.

Ever' spring, though, there were a lot of 'em that came out lookin' 'bout as poor as their horses who'd wintered on a straw pile. It was a crime seein' the way some of those horses were wintered or, for that matter, treated in general.

Pete had got around and bought up some of the better fields of fall wheat for pasture, and we had his steers on 'em. There was plenty enough around to last until snow flew at least, since he'd took the cows and calves to Carey earlier. It was the best kinda fall pasture, and we had all his steers – yearlins, twos, and some smaller threes – on it.

Most of these dry farmers had not much use for a cow, or for that matter, cowboys either. They were all a lot more anxious to farm than build fence and of course a lotta our older cows, not being able to figger what had happened to their old summer homes, took advantage of any holes they could find and mosta the fencin' done wasn't that stout anyways. If there was anything that would get one of those grangers goin' it was seein' cows in a wheat field.

For our part, we didn't think a helluva lot of farmers or farmin' either one. We'd been here first by a long ways, but that didn't really count for much, and you could easily see things were changin' fast and not in the cowman's favor. Mosta those ol' farmers were damn glad to get the twenty-five cents an acre Pete was payin' for the pasture though.

There never was a cowman who loved his cattle any more than Pete. They were a damn fine bunch of near all shorthorn cows. Buyers were always tellin' him they were the best bunch in the country, and Pete, I think, finally got to believin' a lot of it himself. For all the way he loved each ol' cowbrute, he was damn near as helpless horseback as any feller I ever seen, and he left mosta the buckarooin' up to whoever was workin' for him.

He'd always nervous around about somebody eatin' a beef off of 'im, and he'd give me a lotta instructions about keepin' accurate tallies and all, and there was some of them dry farmers that could bear a little watchin'. I kept a pretty close check, as most of the fields were handy to where I was livin' and outside of one or two of the yearlins dying, which was usual, the steers were all gettin' along fine and the count holdin'.

Claude and me and Gene Perkins, a neighbor's kid who helped us some, had moved 'em over to a three twenty that Frank Tucker had just a few days before it snowed, 'long about the middle of November. Tucker was a Palouser and had his fall grain up real good. He was a little more prosperous than most of the breed.

It only snowed three or four inches and then turned colder 'n hell, but we figgered we'd better get the steers on over to the Wood River where Pete had bought hay. I wasn't gonna make the trail over, as Pete had a buncha stuff included some re-ridin' that needed done, but Claude and Card and the Perkins kid were on deck and early the next morning after the snow, we were down gettin' 'em together. Gene hadn't been too keen on makin' the trip, it was really cold, but I'd told 'im if he'd go, I'd let 'im ride my old White Eagle horse and that was all it took.

Anyway, we got the small field gathered pretty quick in spite of the cold. Tucker had come out to help, and we did have two or three half Jersey strays that belonged to a guy on down the base line. Tucker was one of those guys who talked all the time, and he'd been kiddin' us about how much he'd been tempted to butcher one of those fat three-year-olds, but we didn't take 'im too seriously.

We bunched 'em close to the gate leadin' out to the base line an' I cut the strays out. I asked Tucker if he would make sure they stayed back, as I knew they'd be tryin' to follow. He said he would and started the buttermilks off away from the others.

There was a gate onto the base line in the middle of the north fence line, and we moved 'em out onto the road with Claude, who was a good counter, and me on opposite sides of 'em so we could squeeze 'em off a little if needed. Countin' livestock ain't as easy as it looks. You sure gotta keep your mind on. Ya use your hand and count by twos and with two fellers countin' that know how, you won't be far off.

The last of 'em squeeze by, and I get the tally book outta my pocket and ask Claude what he got. He says, "Six hunnert and forty two" which was what we had counted in, by the book. I'd got one less, so we were close, and I mentioned my count to Tucker who'd rode back up while we was easing 'em out and he says, "Now see, if you cowboys can't count closer 'n that, how the hell you gonna know if somebody did slip off with one of them three-year-olds." I didn't say nuthin' back, but I wondered if he'd been countin' and doubt if he'd come within ten if he had been.

Claude had loped on up towards the head of the bunch to watch for open gates and point 'em along, and I told Card and Gene to have a good time and rode on home as I had a lotta things to get done as well as the ridin'.

The next two or three days were busy ones, and I remembered that Pete had made special mention of the fact that Jerry Herbic had not delivered some oats that Pete had made arrangements for, and he'd asked me to see that Jerry got 'em hauled. He'd left all his bulls at the old home place and there were several two and three-year-olds that were kinda poor, and he wanted 'em fed some grain. So one afternoon I rode down to Jerry's place to see about it, and his wife told me he was up Corral Creek at a wood cuttin' camp some of the dry farmers had set up.

The weather had warmed a little, felt like it was gonna snow some more. There hadn't been any more since that first skiff. Since I was saddled up, I thought maybe I'd just ride on up the crik and take a look at the loggin' operation.

I had a good little bitch with me. I never was real strong on dogs, but this was one of the best I ever had. I'd found her and two of her brothers in a sack over in the foothills two or three springs ago. They'd fell off of some camp tender's pack horse, I guess. I felt sorry for 'em and took 'em home. The were just barely big enough to wean, and I fed 'em milk and had no trouble givin' the two dogs away as they were likely-lookin' pups.

The little bitch really took up with me, and I got too attached to part with her. I'd taught her to ride on the back of the saddle. I could stick my boot out a little and tell her to get on, and up she'd come hittin' my foot first and scramblin' right on up. She never barked and was a good heeler, and I got so I really liked havin' her along.

Well, it wasn't hard locatin' the wood camp. I just followed the sled tracks and after a while I smelled wood smoke, and knew I was gettin' close. As I rode up, there was four or five fellers standin' 'round a fire that had a big cast iron pot simmerin' over it. There was a couple of tents set up, and they'd hauled up a little hay and had a team or two tied up and, all in all, it looked like they were really gettin' out the wood.

I'd met two or three of the fellers before, but the reception was about as cool as the weather. They were drinkin' coffee and never offered a cup or nothin', so I just put my hands on the horn and leaned down on 'em, comfortable like, and inquired about Jerry's whereabouts. One of 'em finally said that he was skiddin' the last log or two in for a load and would be in any time.

About then I noticed the bitch had what looked like a big piece of beef that she'd got out of a meat sack that was just layin' on the ground. I stepped off quick and took it away from her and, sure enough, it was most of the steak end of a hind quarter and fat. I walked over to the fire and tried to hand it to a Finnlander that I kinda knew a little, named Costello. He really was actin' odd and says, "That ain't my meat." Well, nobody else offered to take it, so I walked back and picked up the sack and put it back in and laid it on a stump.

This all seemed a little peculiar, but I probably wouldn't a thought much about it, 'cept about then Jerry and a feller named Jack Riley came leadin' their skid teams into camp. While he was still a ways off, this Riley feller looked right at me and says, real low, "Some sonofabitch talked."

Ordinarily, I wouldn't of heard him, but snow on the ground will do strange things with sound sometimes. One thing I know for sure, lookin' back on it, he never figgered on me hearin' 'im. He really was talkin' more to himself, so I said hello to Jerry, and he was at least actin' normal even if he was the only one in the bunch.

I told him Pete was gettin' a little anxious about the oats deal, and he said he had got his wood and was comin' out tomorrow anyway, and would get right to haulin' the oats. Since there still wasn't no invite to supper or anything, I just turned my horse and headed home.

On the way back I see Jonas Carter chorin' around outside a little, so I rode over to his outbuildings to say, "Howdy." We was visitin' along, when we hear a team comin' and damned if it ain't Riley with an empty sled.

He was s'posed to have been a logger from Montana or someplace, and the sled was set up with bunks and corner bind chains and some of them were draggin' and the team was trottin' along like Riley was anxious to get home. I mention to Jonas it's kinda odd to see an outfit goin' out empty, but again don't think too much about it. I tell Jonas I'll be seein' him, and I start on home.

The horse I'm ridin' is a damn good walker, but I never ketch up with Riley. I get to thinkin' things over, clear back to Tucker kiddin' about butcherin' one of Pete's three-year-olds and the look Costello had on his face when I handed him the chunk of beef. It dawns on me that there's some dry farmers eatin' better beef than any of 'em was accustomed to.

Well, I had a hard time gettin' to sleep thinkin' about it. Rustlin' or butcherin' for that matter was nothin' to joke about. The legislators had been under a lotta pressure from some of the cattle associations that had come together, mostly to fight the sheepmen, but there was stealin' goin' on all the time, and the sentencin' had been tightened up to where it could be for as much as thirty years if it was proved.

The next morning I can see it's gonna snow some more, and I get to thinking it's been a week or more since we'd had any and maybe for the helluva it I'd just ride down to that field of Tucker's and see if I could see any tracks.

I saddled a horse and rode over to Tucker's house first, but there was nobody home. He was makin' an overnight trip to Hailey for winter supplies I found out later, so I just helped myself to the field where the steers had been and begin lookin' at horse tracks.

As I say, there hadn't been no new snow and the wind hadn't blowed, so everthin' looked pretty fresh, even yet. Of course there was a lotta cow tracks ever'place in the field. But most of them were made while they were grazin' and quiet.

It was easy to pick out Tucker's horse tracks of the morning he'd helped us move out. All of our horses had been shod up 'til it snowed, and we'd had to pull the shoes, and their hooves were trimmed up nice. Tucker's horse hadn't been shod for some time, and the tracks were kinda wide and spread out.

It'd been impossible, of course, to have seen any tracks if he'd took a steer out the same gate we'd used, but I remember seein' another gate on the North-South road that run down the east side of Tucker's field and led right by the place Riley was livin' on. In fact, he was one of Tucker's closest neighbors.

I ride on down towards this gate watchin' the ground as I go and, when I get about there, sure enough, I see another set of horse tracks sometimes mixed up with Tucker's horse's. I slow up and really follow and look now, and I can see that they're doin' some chousin' as ever so often there's signs where a horse had setup and turned. I begin to see a certain steer track more and more that's also on the run, and pretty soon I see where the strange horse had been in a ropin' and, hell, it's all there - plain as if it had been wrote in a book. Tucker and some feller had been tryin' to drive one of the bigger steers outta the field into the road, and they'd had trouble and the other feller had roped 'im and, that way they was able to get it done.

I follow the tracks on out through the gate where they'd turned south towards Riley's, and there on the road there'd been enough travel to make it harder to follow, but still I can see the same steer's track ever' now and then. I ride on past Riley's house and the sign quits, so turnin' back I ride into Riley's yard and step off and knock on the door.

After a little while Riley's wife comes to the door. This is the first time I'd seen her, and she looked like she had the weight of the world on her shoulders. She's small and skinny and there's at least four or five kids peekin' out around her skirts.

I ask if Riley is around, and she says he's had to leave for a day or two, but she's expectin' him back most any time and wonders how she could help me. I tell her that we'd had steers in Tucker's field and the count had slipped a little and am wonderin' if they'd mighta seen some get out or go by or somethin'. She don't turn a hair and says that, no they'd not seen any stray steers, and I feel kinda bad to even talk about somethin' like this to a woman, let alone one who looks as wore out as she does.

Well, I tip my hat and tell her thanks and, as I ride out, I go a little out of the way to get a look at six or seven horses that are the other side of the barn. They're all draft stock, and I see pretty quick that the horse that done the ropin' wasn't with 'em. The chances are pretty good that Riley has rode 'im off to wherever he went.

I ride on home thinkin' maybe at least them little kids is gettin' their bellies full of beef, and when I get there, who do I see but Pete. He'd drove over with a light pair of bobs to get some stuff out of the wagon and see how we was doin' with his thin bulls.

I tell 'im the whole story from start to finish, and he gets pretty excited, as I knew he would, and says, "By God I'll have them two sonsabitches pinched." On his way back through, he goes to Hailey and signs out a complaint about losin' the steer.

Nothin' much happens for a few days except it snows a foot or so. Herbic brings a load of oats over, and I try 'im out a little to see if he'll say anything, but while he's plum friendly. He's enough dry farmer that he ain't sayin' nothin' about beef – 'specially stolen beef.

A couple more days go by and who shows up but a deputy sheriff over from Hailey. I'd never met 'im before, but he ain't a bad feller, and we have a pretty good visit while I'm tellin' 'im what I know. He's got a search warrant for Riley's place and wants to know if I'll go down there with 'im. While I just ain't real anxious thinkin' about that woman and little kids, I say I will and I saddle a horse and we head off to Riley's. I show 'im the field the steers were in and the gate where Riley and Tucker had took the steer out of the field. With the fresh snow there's no tracks to look at now.

We get there and of course the same woman, an' what seems like even more skinny little kids, come to the door. She tells us that Riley is still away, and that she ain't real sure when he'll be back now, although it shouldn't be too much longer. The deputy explains in a fairly decent way that he's got a search warrant and that he's gonna look around outside some, and she don't say much but kinda mumbles somethin' about helpin' ourselves.

The deputy's real business-like, and we start right in with the barn. He says we're lookin' for the hide first or some evidence showin' there was somethin' butchered lately. He don't go into too many particulars, but I help as best I can. The barn ain't really too old, but there's a lotta junk piled up in some of the stalls. We don't turn up a thing suspicious, but I remember I'm surprised that there is as much good harness and collars and double trees and stuff as there was.

Most things in the barn looked pretty bleak. There's a little dab of wheat hay in the loft and a few oats in a bin. We stir both the hay and grain up a little, but don't find nothin'. There's another shed or two, and we poke around in one that's bein' used for a kinda shop. Again, I'm surprised at the number of crosscut saws and axes and cant hooks as well as some chain and other loggin' stuff that there is in this one shed. I wonder at the time if some loggin' outfit ain't been relieved of all this stuff.

By now we've pretty well covered all the outbuildings, but there is a little cellar and, of course, the shack they're usin' to live in. The deputy says we better go look in the house first, and when we knock again the woman comes to the door, and when he says he's sorry but we're gonna have to look in the house, she thinks a little and says, "What are you lookin' for, a hide?" This takes both of us plum by surprise, but the deputy tells her yes. So she goes and puts on an old mackinaw that's probably Riley's and heads right out to the one shed.

We follow along behind and before you know it she's rasseled a 30 gallon wooden barrel out from under a bunch of stuff and tippin' it over on its side begins to paw more junk outta it 'til at the very bottom you can see a red hide. She says, "There's your hide" and turns and walks back to the house.

Well, we're both pretty surprised, but sure enough there's a hide although its froze up stiff as a board the way it had been folded up to go in the barrel. I straighten up the barrel and throw the junk back in it while the deputy is workin' at the hide. It's impossible to unroll it, and finally I remember there's an outside pump on a well. So takin' the hide over to the well, we pump water on it for a while and thaw it enough that we can begin to tell which end is which anyway. The rear end thaws first and pretty soon I can see that a foot square chunk of the hide over the left hip is missin' and of course that's where Pete's Y shoulda been.

Well with the kinda luck we're havin' findin' things, searchin' for a foot square piece of rawhide seems pretty nigh impossible, and I can see the deputy's thinkin' the same thing. With some trouble we finally get the hide folded up tight again and on the back of the deputy's saddle. His horse is pretty gentle, but not that gentle. Anyway, he says we got some good "evidence" and he's gonna head on back to Hailey, although he'll stay overnight in Soldier.

As we ride up towards the base line road I ask 'im what'll happen next, and he says that probably the court will issue an arrest warrant for Riley and maybe even Tucker. I ask 'im if he's gonna search Tucker's, and he says he ain't got a warrant for that and, anyway, it'd be hard even if we find a quarter of beef to prove where it came from.

Well, a week or so goes by and one day who should ride up just as I'm fixin' me a little dinner, but Tucker. I ask 'im to get down and have a bite with me, and he does. He starts out askin' if Orly had been over and left a check or anything and talks along about this and that like he always does. I figger he's wantin' mostly to know what's goin' on as I know for sure the talk's pretty much all around about the missin' steer.

I just don't feel like fillin' 'im in on things, so keep fairly quiet. Finally, he says, "I hear some talk about Orly thinkin' somebody maybe butchered a steer while they was in my field." I says back, "From the looks of the tracks comin' outta yer east gate, it'd peer like maybe they did."

Tucker all of the sudden looks like maybe he wished he'd not brought the subject up. I don't say nothin' more and since we're through eatin' Tucker says it's time he was gettin' on back and nuthin' more was said. I make a point of tellin' him Orly will be sure and drop off a check the next time he's over.

I guess it's my time for company cause the next day three of the dry farmers I kinda know show up. It's well after dinner this time, but I can see they wanna visit and since it's colder than hell, I ask 'em in the house and build up a good fire.

It don't take 'em long to get to the point of things. They tell me that they been circulatin' a petition around the country askin' for Orly to drop the charges on Riley. They say its been well signed too. Seems as tho' some of 'em know that Riley took off because he figgered the 'big cowman' was goin' to have 'im pinched and that the circumstances he left his family in was pretty bad, and they figger if Orly would drop the charges Riley would come back and the family would be a lot better off.

Well, I don't disagree with 'em any about the woman and kids. God knows they look like someone ought to be lookin' after them. I do tell 'em though, that Orly would probably be a whole lot keener to drop charges if he had the forty dollars the steer was worth in his pocket. This started 'em off about how nobody could know for sure who'd done what, and I just tell 'em that the hide and the tracks were good enough for me. But I do go ahead and tell 'em to write to Pete and see what he says.

In not long, Orly comes over again and tells me he guesses he will go ahead and drop the charges. He's a little sensitive about bein' a 'big mean cowman' pickin' on women and kids and says Riley's wife and kids are pretty hard up and maybe hungry an' all.

He says some of 'em are gonna try to take up a collection for the woman, and if they do well enough they'd try to pay 'im for the steer even. It really don't matter a helluva lot to me one way or the other, and I tell 'im the same. Anyway, he goes ahead and drops the charges at the Hailey Court House on his way back through and, sure enough, in about a week I hear Riley shows back up.

Now it's the cowmen's turn to get upset. There's talk around that, by god, it wasn't long ago that they woulda handled both Tucker and Riley with a good tree limb and a couple of lass ropes. This talk goes on a while, and the next thing I hear is that both Tucker and Riley have been pinched.

The Blaine County Association's directors signed another complaint and hired a detective. Seems as tho' when the deputy pinched Riley, he told 'im Tucker was as guilty as he was and a whole lot more. Anyway, they was both jailed 'cept of course Tucker got out on bail right away, while Riley couldn't make bail and the farmers had to start another pot, which they did and finally got 'im out on bail too. By this time it's well into the winter.

Then one day along towards spring the deputy shows up with a subpoena for me and says the trial is gonna start next week in Soldier, and I'm to be the prosecutor's best witness and all. Seems like Tucker's hired himself a pretty good lawyer from some place, and this lawyer had made sure the trial would be in Soldier, closer to home, where maybe he could get a bunch of dry farmers on the jury. Anyway this is what the talk is around Soldier and Hailey according to the deputy, and I don't know because I been too busy to go to town much.

Well, fairly early the next mornin' who shows up but Tucker ridin' the same ol' horse. I'm just startin' on a load of hay outta the stack close to my shack, and he sees me and comes riding out. Damned if he don't pick up an extra fork I got on the sled and get up on the stack and help me load. It's one of those nice sunny days you can sometimes have in late winter with a few Blackbirds back and singin' and the sun feelin' like the sun again.

After we've got a load, we sit on the side of the stack and right off Tucker asks me if I am gonna be at the trial. I don't figger it'll hurt much to tell him I am, and I do. Course then he wants to know just what I saw in the way of tracks and things. The funny thing is he seems to think I'm really on his side, or at least he lets on like he does.

I don't tell 'im much, but I let 'im know that I figger he's been in on it, and I don't much give a damn what he thinks. He finally gets back on his horse and rides off. I figger the lawyer probably put 'im up to it, and I hope I didn't help 'em any. I've told several people by now about the two sets of horse tracks, and I'm pretty sure Tucker knows anyway. He was just trying to feel me out, I guess.

Well, I make arrangements with Card to do the feedin' for me, and early the mornin' of the trial I ride down to Soldier. I figger on gettin' a good breakfast at Goldie Barrett's restaurant and damned if it ain't so crowded I can hardly git sit down. A lot of people are in town as seems it's pretty excitin' for ever'one to have a couple of dry farmers on trial for killin' a beef.

Two of the Association's directors from over on the Wood River are at a table and motion me over, and I'm glad to have a place to sit down. After shakin' hands, they want me to run through what I'm gonna say on the witness stand, and I tell 'em the story again for by now I got it learned by heart.

They wonder if there'd be any chance of comin' on that piece of hide with the brand at Riley's if the place really got tore up. I tell 'em that it probably went in a hot stove the same night it was cut out and, that as far as I could see, it would be a waste of time. They seem to figger I'm probably right.

About nine we walk on over to the hall they're holdin' the trial in, and it sure is fillin' up. The day is nearly all spent on pickin' the jury with the lawyers both payin' close attention. Tucker's lawyer comes from Mountain Home, I hear, and he seems pretty smart and asks all the intended jurors a lotta questions on how they feel about homesteadin' and the rights of cowmen and stuff.

The other lawyer don't do much questionin' but it still takes all day to get the jury picked. It's kinda an assortment with six or seven farmers and two ranchers and the rest townspeople. I only know the ranchers and two of the people from Soldier just to show you how fast the country is changin'.

The Prosecuting Attorney finds me after they shut down and takes me over to the city hall where he's got a kinda office. He asks me what all I know about the deal, so I go through the story from start to finish another time except with him asking a lot more questions especially about how I could tell one horse's tracks from another. The feller's pretty green about trackin', but he can tell how certain I am of what I seen and seems satisfied.

Since I'm gonna be the first witness the next mornin', I decide I'll get me a room over at the old Wardrop Hotel and save the ride home and back. The hotel's pretty full, but they find a room for me, and I spend the evenin' over at the saloon visitin' with folks from all around and have an enjoyable time.

The trial gets goin' again the next mornin' and, sure enough, the Prosecutor calls me first and I tell the story again with him asking each question and the other attorney objectin' ever now and then, and it takes what seems like a long time. After he's through, Tucker's attorney starts in on me and asks a lot of questions about how I can be so sure of the horse tracks. I'm bein' pretty careful, and he never really trips me up, but finally damned if he don't ask to bring in the hide me and the Deputy had found. It'd been thawed and stretched and was pretty dry by now.

The lawyer says, "Now, Mr. McCarter you tell me if there is anyway you can identify the hide as bein' one of your brother's steers other than by the brand, which we can all see is clearly missin'." Well, the hide is just a pretty common sort of shorthorn hide. The steer had more white on the belly and sides that you'd ordinarily see, but the lawyers got me. There ain't no way I'm gonna convince somebody I could recognize that hide, even if I'd raised the steer on a bucket. I tell 'im the same, that I can't prove it was one of Orly's, but that it could sure have been because it looked about like any of several hundred more he had.

He says this ain't good enough, but there is one thing I'd noticed and I go ahead and tell 'im that it's pretty plain two fellers had took the hide off. I'd got a good look at the flesh side of the hide when he'd had it carried up to where I was sittin'. One side of the hide had been skinned off by somebody who really knew how to skin a beef. The hide was smooth and white with no cuts, while the other half looked like hell. There'd been fat and meat left on the hide all over, and I could see a place or two where the hide had been cut through. But the lawyer says this ain't relevant either, and that finishes up my turn in the witness chair.

The next witness is the deputy that had found the hide, and then came the detective that the association had hired, and he hadn't been able to come up with much of anything. Then they had the defense witnesses who mostly tell what fine fellers Tucker and Riley are and finally the trial is wound up and the jury goes out just as its quittin' time anyway.

I figger I just as well stay around 'til mornin' and see what the verdict is gonna be, so I go back over to the hotel and make sure I got a room again. There's a lotta talk around in the restaurant and saloon about what ever'body said at the trial and ever'body's guessin' about how each one of the jury is gonna vote, and I understand Tucker and Riley are both worried as hell.

Anyway, I've just finished breakfast over at Goldie's the next mornin' and when I'm leavin' Tucker, who's sittin' alone at one table, motions me over and asks me to sit down. He starts out sayin' he sure hopes Orla and me ain't sore at 'im as he'll have pasture to sell this fall, and I can see the rumor about him bein' so scared is maybe a little off.

He goes on talkin' like he always does with me not sayin' much, when all of the sudden I hear 'im say that he ain't too worried about how this is gonna turn out as he had slipped Judge Lightfoot $250 before the trial had begun. This really surprised me, and I could't help but say, "Where the hell did you get $250?" Well, he tells me he'd borrowed part from a brother still up in the Palouse country and part from the bank on his comin' crop.

I get to thinkin' about what all the judge had told the jury after the trial was done, and it did seem like he was being pretty hard on the prosecutor, but of course I really didn't know much about how things like this are done.

Well, sure enough, when the jury comes back in about mid-mornin' the verdict is not guilty. While I never had got too worked up about the whole mess, I can't help but be some disappointed because of the time I'd put in bein' wasted and all. As I'm walkin' back over to the livery barn for my horse, who should come steppin' up to me in his little frock coat an' all but Judge Lightfoot. He says, "Bill, ya know if there'd been anything about that hide you coulda identified, we'd sent them two rascals away."

Now I'm thinkin' about the first year I'd worked out for McMahon and he'd paid me just a little over $200, and for the first time in the whole deal I'm really mad. I says, "Yeah Judge, but that $250 of Tucker's woulda probably made a pretty short trip outta it." He couldn't been more surprised if I'd slapped his face, which had turned real white, and he spun around on his heel and took off like a scalded cat.

Well, this about winds the story up. That fall I run into Riley up Corral Creek. He's lookin' for a place to get out firewood again he says, so I stop and visit awhile. The talk drifts around to the trial and he tells me the story.

Accordin' to Riley it was all Tucker's idea. The day it snowed, he comes to Riley's place and tells him with the snow comin' it won't be long before we take the steers out. It'd be a shame to miss such a good chance at one of them fat three-year-olds. Tucker's got a quart of whiskey with 'im and, according to Riley, is two-thirds drunk already. They finish the quart and feelin' bold, they saddle Riley's horse and start off.

Riley says that Tucker, even with the whiskey, is pretty scared and when the steer gives 'em a run, wants to quit. But by this time it's gettin' dark and still snowin' a little and Riley tells 'im nobody is gonna see 'em and while Tucker braves up a little, he still ain't no help, and Riley finally has to rope the steer to get 'im outta the field. Riley says Tucker's even less help gettin' the steer butchered.

After all, it was kinda good to know at least I'd read the sign right. Riley said as much and, all in all, he's a better feller than Tucker. Although I found out later, after we'd moved to the Montana, that Riley had logged around the Flathead and, sure enough, was suspected of gettin' away with a whole loggin' camps tools and harness.

'Bout the last time it ever come up was two or three years later when I'm helpin' with a threshin' crew. By this time I'm married and half turned to farmer myself. Anyway, we're all eatin' dinner outside at two big tables that the womenfolk had set up. There musta been twenty five or thirty fellers all set down 'an eatin' away, when Riley looks over at Tucker, whose at the end of the other table and says, "Hey Tucker, what say you and me get one of McCarter's beeves again this fall?" Tucker looked like he'd like to go under the table for a while, and ever'body had a big laugh.